OpenLCB Programmer’s Guide

by John Socha‑Leialoha

This edition is current as of 2025-12-23.

I wrote this book to help developers get started with OpenLCB. I used GitHub Copilot to help draft the text; during writing Copilot was provided access to the OpenMRN and OpenMRN‑Lite source code, the NMRA LCC standards, and NMRA LCC technical notes to assist with examples and explanations.

The source for this book is available at the project’s GitHub repository: openlcb/OpenLCB_Technical_Introduction.

Feedback and contributions are welcome — please open an issue or submit a pull request on the repository’s issues page: openlcb/OpenLCB_Technical_Introduction issues.

Documentation Copyright © 2025 John Socha‑Leialoha. See the repository for license details: LICENSE_DOCS.md and LICENSE.

Introduction

Purpose

The purpose of this book is to help you get up to speed on OpenLCB so you can start creating LCC products. There are a lot of concepts and we’ll go into just enough depth to get you going, without bogging you down with all the details and possibilites. The standards and the technical notes have a lot more details.

Focus of this book

We’re going to focus on how to create a device (node) that can be added to an OpenLCB network. To make learning easier, we’ll start with WiFi/TCP transport, which allows you to see network traffic easily and test without special hardware. Later chapters will cover adding CAN bus hardware for traditional LCC installations.

Assumptions

We’re assuming you’ve used LCC products, and therefore already understand concepts like the producer-consumer model. We also assume you’ve written code for microcontrollers and have worked with I/O pins.

About Names

Let’s start with what to some might be confusing—the names LCC vs OpenLCB. LCC is a brand name owned by the NMRA. It covers a set of standards that have been adopted by the NMRA for Layout Command Control (hence the LCC).

OpenLCB is the name of the working group that created the standards approved by the NMRA and continues to create new standards. This is a group of dedicated volunteers who are working to fulfill the dream.

You’ll notice that the standards use the name OpenLCB everywhere except for the header at the top of the document. In this book, as in the standards, we’ll use the term OpenLCB everywhere except this page.

Node

A Node is the basic building block of an OpenLCB network. It’s a device that can send and receive OpenLCB messages. We’ll describe these messages in more detail in a later chapter.

Each node has a unique 6-byte ID that must be assigned by the manufacturer. We’ll describe in a later chapter how you can get your own set of IDs to use in your products (or DIY boards).

Transport Layers

OpenLCB is designed to work over different physical transport layers. The two main options are:

CAN (Controller Area Network): The traditional transport for OpenLCB, used in most commercial LCC products. CAN uses a two-wire bus with excellent noise immunity and built-in arbitration, making it ideal for model railroad environments. It requires CAN transceiver hardware and proper bus termination.

WiFi/TCP: An alternative transport that uses standard WiFi networking and TCP/IP. This is particularly useful for development and learning because:

- No special hardware required beyond WiFi-capable microcontrollers

- Easy to monitor traffic using standard network tools

- Can connect to JMRI and other tools over your home network

- Simplifies initial prototyping and testing

In this book, we’ll start with WiFi/TCP transport because it’s more accessible for learning. Once you understand the core concepts, the principles transfer directly to CAN-based implementations. Future chapters will cover adding CAN hardware.

Both transports use the same OpenLCB protocols and message formats—only the physical layer changes.

Network Architecture

An OpenLCB network is made up of participants with different roles. The two primary roles are:

Nodes — devices that produce and consume events. Each node has a unique identifier and announces itself during startup.

Hubs — services that route and forward messages between participants. A hub may be implemented differently depending on the transport (for example, as a network server for TCP-based transports or as a bridge to a CAN bus). Hubs are optional in some deployments; on shared physical buses messages are exchanged directly between participants.

A single device can implement both node and hub functions. Examples in later chapters show convenient development setups where one device acts in both roles, but the concepts below are transport-agnostic.

Here’s a conceptual architecture diagram:

graph TB subgraph DeviceA["Device A"] NodeA["Node A<br/>(produces/consumes events)"] end subgraph Hub["Hub (optional)"] Router["Message Router / Hub"] end Monitor["Monitor / Tool<br/>(optional)"] DeviceB["Device B<br/>(other node)"] CAN["CAN Bus (optional)"] DeviceA ---|messages| Router DeviceB ---|messages| Router Monitor ---|connects| Router CAN -.->|physical transport| Router style DeviceA fill:#e1f5ff style NodeA fill:#fff9c4 style Hub fill:#f3e5f5 style CAN fill:#eeeeee style DeviceB fill:#eeeeee

What this shows:

- Node: Produces and consumes events and announces itself on the network during startup.

- Hub: Forwards messages between connected participants and may accept connections from monitoring tools.

- Monitor/Tool: Observes network traffic and can send test messages.

- Future Expansion: Multiple nodes and transports (e.g., CAN bridges, network servers) can be integrated behind hubs.

Why this design works:

- Separation of concerns: The messaging protocol is transport-agnostic; nodes, hubs, and tools speak the same message formats regardless of physical layer.

- Scalable: Hubs enable multiple devices and tools to interconnect without changing node implementations.

- Flexible: Hubs can be implemented differently per transport, allowing the same protocol to work in embedded, wired, and networked environments.

Platform and transport choices (for example, why this book uses ESP32 and WiFi/TCP for early examples) are discussed in Chapter 2 (Getting Started).

Introduction to CAN

Controller Area Network (CAN) is a standard that was initially created in 1981 by Bosch, and has since been used for factory automation and communication networks in cars, to name just a few uses. Today there are hundreds of billions of devices using CAN bus in daily use.

As a result, there are a number of relatively inexpensive ICs available that fully implement the CAN specifications out of the box. By using CAN controllers and drivers, you do not have to write highly time-sensitive code. Instead, you can focus on implementing support for the messages in the application layers, which is a “relatively” simple task compared with implementing a transport layer.

CAN Messages

CAN transmits messages, called frames on the bus. Every other device (node) on the bus can (and must) listen to all of the traffic on the bus. One of the interesting and useful aspects of CAN is how it handles collisions, which is through arbitration.

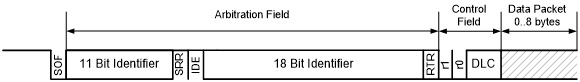

CAN frames, in the form used by OpenLCB, consist of a 29-bit header followed by zero or more bytes of data. This is using the extended frame format, also know as CAN 2.0 B.

Arbitration

Arbitration is the process used to ensure that only one message is being transmitted at one time. If two nodes are trying to transmit different messages at the same time, one of those two will pass through the bus unharmed, while the other node will realize it lost the arbitration and attempt to re-transmit right after the first message is completed. This allows nearly 100% utilization of the bandwidth, because the node(s) that lost the arbitration will immediately stop, thereby not corrupting the frame that is being transmitted by the winner of the arbitration. This guarantees forward progress. In contrast, old style Ethernet (and LocoNet, btw.) uses a more complex scheme, where a collision destroys the frame, then nodes have to back off, wait a random period, then attempt to transmit again, thus wasting bandwidth.

The arbitration phase relies on drivers only pulling the bus low. If two nodes attempt to put different bit values on the bus at the same time, the 0 will always win. Here is a chart that shows how this works:

| Node 1 | Node 2 | Bus Value |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

Dominant and recessive are the normal terms used because a ‘1’ bit (recessive) does NOT drive the bus. It allows the terminators to ‘drive’ the bus by pulling the two bus lines to a common voltage. (2.5V) On the other hand a ‘0’ bit (dominant) drives the bus to both high and low. (CANH goes to 5V and CANL goes to 0V) The bus drivers can always over power the terminators, and that is how the zero bit always dominates over the one bit. It also explains why at least some termination is required. The termination values are also chosen to suppress cable reflections, but that is actually only an issue on long lines. Also note that this explains the complexity of our RR-CirKits terminators. You can attach a logic analyzer to one of our terminators because it creates a logic level image of the bus (to drive the activity LED). You cannot connect a logic analyzer directly to the CAN bus, because it does not contain a logic level signal on either line.

Normally two nodes will happily send identical data until one node or the other transmits a zero bit during the other node’s one bit. At that point the recessive node notices that it transmitted a one bit,but received a zero bit back from the bus. This tells the recessive node that it is in conflict and must immediately stop transmitting. No other nodes can observe that this happened. This requirement for an immediate (within a fraction of the bit time) response is what limits the CAN bus segment lengths.

– Dick Bronson, RR Cirkits

Arbitration uses the 29-bit header value as a priority value to gain access to the bus, where lower values have higher priority. This mechanism provides very high utilization of the bus’ bandwidth because one node will always win a collision and keep transmitting. In contrast, Ethernet uses a more complex scheme where nodes have to back off, wait a random period, then attempt to transmit again, thus wasting bandwidth.

For arbitration to work sucessfully, each message sent by a node needs to use a unique 29-bit ID. The details for this are handled by the OpenLCB specifications, and are different for different types of messages.

Node Startup Sequence

When an OpenLCB node powers up or resets, it goes through a defined startup sequence to join the network. Understanding this sequence is essential to building your own nodes.

Note for Library Users: If you’re using OpenMRNLite or other OpenLCB libraries, all of the mechanics described in this chapter are handled automatically for you. You don’t need to implement alias reservation, collision detection, or recovery—the library does it all in the background.

This chapter exists to help you understand how it works, which is valuable knowledge when debugging network issues or designing advanced features. However, if you just want to build a working node with async_blink_esp32, you can skip straight to Chapter 3 without missing anything essential. The library takes care of it.

What Happens During Startup

Every node follows this sequence:

-

Check ID (CID): The node sends four CID frames containing its 6-byte unique Node ID, spread across the frames. This allows the node to check if anyone else is using its desired alias.

-

Reserve ID (RID): If no other node objects, the node sends an RID frame to reserve its chosen 12-bit alias for the Node ID.

-

Alias Map Definition (AMD): The node announces the mapping between its full 6-byte Node ID and the 12-bit alias it just reserved.

-

Initialized (Init Complete): The node sends an “Initialized” message telling the network it’s now fully online and reachable.

sequenceDiagram

participant Node as New Node

participant Bus as OpenLCB Network

participant Others as Other Nodes

Note over Node: Power On / Reset

Node->>Bus: CID Frame 1 (Node ID bytes 0-1)

Node->>Bus: CID Frame 2 (Node ID bytes 2-3)

Node->>Bus: CID Frame 3 (Node ID bytes 4-5)

Node->>Bus: CID Frame 4 (checks alias)

Note over Node,Others: Wait for conflicts (200ms)

Node->>Bus: RID (Reserve alias)

Node->>Bus: AMD (Map Node ID to alias)

Node->>Bus: Initialized Complete

Note over Node: Now reachable on network

Node->>Bus: Producer Identified (events)

Node->>Bus: Consumer Identified (events)

Why Use Aliases?

OpenLCB uses 6-byte Node IDs to ensure every device in the world has a unique identifier. However, CAN bus headers only have 29 bits available. To fit the sender information plus message type, OpenLCB uses temporary 12-bit aliases that represent the full Node ID during a session.

This alias negotiation happens every time a node starts up. The aliases are not permanent—they’re regenerated each time the node powers on.

Node Participation

Other nodes on the network listen during this startup sequence. If another node is already using the alias the new node wants, it will send a conflict message, forcing the new node to pick a different alias. This ensures all active nodes have unique aliases.

Multi-Node Network Behavior

The startup sequence isn’t just about a single node announcing itself—it’s a conversation with the entire network:

Other nodes participate by:

- Listening to all CID frames to check for alias conflicts

- Responding with conflict messages if their alias is being claimed

- Recording the Node ID to alias mapping from AMD frames

- Acknowledging new nodes with responses to queries

This cooperative behavior ensures:

- No two nodes ever use the same alias simultaneously

- Nodes can discover each other’s capabilities

- Gateways and bridges can manage routing efficiently

- Network monitoring tools (like JMRI) can track all active nodes

When your node starts up, it’s not alone—the entire network is watching and ready to help it join successfully.

What Happens When Things Go Wrong

The startup sequence above describes the happy path—when everything works perfectly on the first try. In practice, nodes must be prepared to handle conflicts and retries.

Alias Collision Detection

If another node on the network is already using the alias your node wants to reserve, that other node will respond to your CID frames with a Reserve ID (RID) frame. This signals a collision:

-

During CID phase: If you receive an RID while sending your CID frames, your chosen alias is already in use. Your node must:

- Abandon the current alias

- Generate a new tentative alias

- Start the entire CID → wait → RID sequence over from the beginning

-

During the 200ms wait: If another node transmits any non-CID frame using your tentative alias, you know there’s a collision and must restart.

Here’s what the collision and recovery process looks like:

sequenceDiagram

participant Node as New Node

participant Bus as OpenLCB Network

participant Other as Node Already Online

Note over Node: Generate Alias ABC

Node->>Bus: CID Frame 1 (with alias ABC)

Other->>Bus: RID (Collision!)

Node->>Node: Detect Collision

Note over Node: Collision detected!<br/>Generate New Alias DEF

Node->>Bus: CID Frame 1 (with alias DEF)

Node->>Bus: CID Frame 2 (with alias DEF)

Node->>Bus: CID Frame 3 (with alias DEF)

Node->>Bus: CID Frame 4 (with alias DEF)

Note over Node,Other: Wait for conflicts (200ms)

Note over Other: No conflict, silent

Node->>Bus: RID (Reserve alias DEF)

Node->>Bus: AMD (Map Node ID to alias DEF)

Node->>Bus: Initialized Complete

Note over Node: Now reachable with alias DEF

Your node’s alias generation algorithm (described in section 6.3 of S-9.7.2.1) ensures that each collision produces a different alias candidate, so nodes won’t get stuck in a loop trying the same alias repeatedly.

AMD and Alias Validation

Once you’ve successfully reserved an alias and sent your AMD (Alias Map Definition) frame, the alias mapping is established. However, your node must remain vigilant:

-

Alias Mapping Enquiry (AME): Other nodes can query your alias at any time using an AME frame. Your node is expected to respond with another AMD frame confirming the mapping.

-

Duplicate Node ID Detection: If your node receives an AMD frame from another node claiming to have the same 6-byte Node ID as you, this indicates a serious problem—two nodes with identical IDs exist on the network. Your node should:

- Signal this condition to the user (LED blink pattern, log message, etc.)

- Optionally transition back to the Inhibited state

- Restart the alias reservation process with error handling

Collision Recovery in Your Code

When implementing your node:

- Always expect CID collisions - Your initial alias choice might conflict; be prepared to generate alternatives

- Implement retry logic - After detecting a collision during the CID phase, generate a new alias and restart

- Validate on receipt - When receiving AMD frames from other nodes, check for duplicate Node IDs

- Handle AME queries - Always respond to AME frames with AMD frames to maintain alias mappings

Most of this is handled transparently by OpenMRNLite, but understanding these scenarios helps when debugging network startup issues.

Note: For implementation details on alias collision handling and retry algorithms, see the async_blink_esp32 example code in Chapter 3, which demonstrates how OpenMRNLite handles these scenarios automatically.

References

For detailed protocol specifications, see:

CAN Frame Transfer (Node Startup Sequence)

- S-9.7.2.1 CAN Frame Transfer Standard - Normative specification for CID, RID, AMD frames and the 200ms wait requirement (section 6.2.1)

- TN-9.7.2.1 CAN Frame Transfer Technical Note - Background and examples

Message Network (Initialization Complete)

- S-9.7.3 Message Network Standard - Normative specification for Initialization Complete message (section 3.3.1) and message network protocol

Note: Future chapters will dive deeper into how the alias generation algorithm works and how to handle collisions in your code.

Events and Run Mode

After a node completes its startup sequence, it enters “run mode” where it actively participates in the network by producing and consuming events.

What is Run Mode?

Once a node is initialized and online, it:

- Produces events in response to physical inputs or internal state changes

- Consumes events from other nodes to control outputs or change behavior

- Responds to queries from other nodes about its capabilities and status

- Maintains its network presence by keeping its alias active

This is the normal operating state where your node does useful work on the layout.

Event Flow Example

Here’s a simple example of how events flow between nodes in run mode:

sequenceDiagram

participant Button as Button Node

participant Network as OpenLCB Network

participant LED as LED Node

Note over Button: User presses button

Button->>Network: Produce Event<br/>05.02.01.02.02.00.00.01

Network->>LED: Event received

Note over LED: LED turns ON

Note over Button: User releases button

Button->>Network: Produce Event<br/>05.02.01.02.02.00.00.00

Network->>LED: Event received

Note over LED: LED turns OFF

In this example:

- The button node monitors a physical button

- When pressed, it produces an event with ID

05.02.01.02.02.00.00.01 - The LED node is configured to consume this event

- When it sees this event on the network, it turns on its LED

- A different event ID (

...00.00.00) controls the LED turning off

Producer/Consumer Model

OpenLCB uses a producer/consumer event model:

- Producers send events when something happens (button press, sensor trigger, timer expiration)

- Consumers listen for specific events and react to them (turn on LED, throw turnout, sound horn)

- A single node can be both a producer and consumer of different (or even the same) events

This decoupling is powerful: producers don’t need to know who’s listening, and consumers don’t need to know where events come from. You can reconfigure your layout by just changing which nodes consume which events.

Event Identification Messages

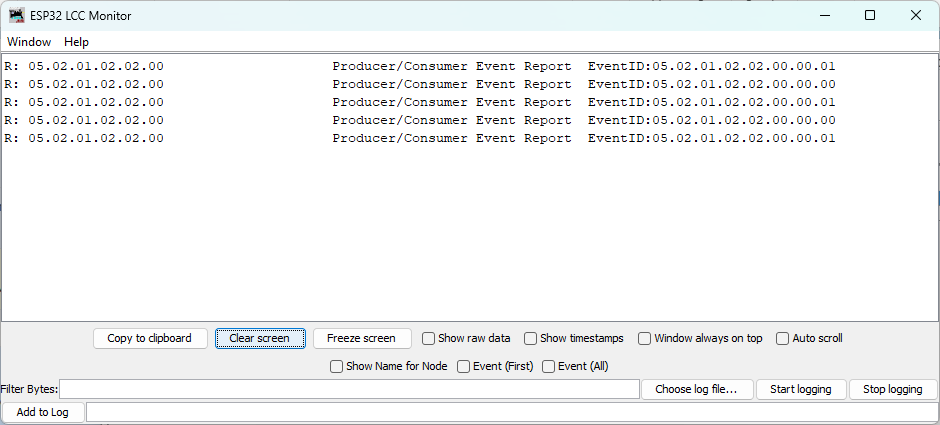

Part of the startup process includes announcing what events a node produces and consumes. The async_blink example sends these messages after completing initialization:

Producer Identified Valid: Event 05.02.01.02.02.00.00.01

Producer Identified Valid: Event 05.02.01.02.02.00.00.00

Consumer Identified Valid: Event 05.02.01.02.02.00.00.01

Consumer Identified Valid: Event 05.02.01.02.02.00.00.00

This tells the network: “I can produce these two events, and I can also consume the same two events.”

The “Valid” state means the node is actively configured to use these events. “Invalid” would mean the event is known but not currently in use.

Async Blink Events

Let’s look at what the async_blink example does in run mode. It’s intentionally simple to demonstrate the concepts:

Every second, it alternates:

- Produce event

05.02.01.02.02.00.00.01(the “1” event) - Because it also consumes this event, its own LED turns ON

- Produce event

05.02.01.02.02.00.00.00(the “0” event) - Because it consumes this event too, its own LED turns OFF

This creates a blinking LED controlled entirely through OpenLCB events, demonstrating the producer/consumer model in a single node.

In a real layout, you’d typically have separate nodes for inputs (buttons, sensors) and outputs (LEDs, turnouts), but the event flow works exactly the same way.

For detailed event protocol specifications, see:

Note: Future chapters will show you how to create your own nodes with real button inputs and LED outputs on an ESP32 microcontroller.

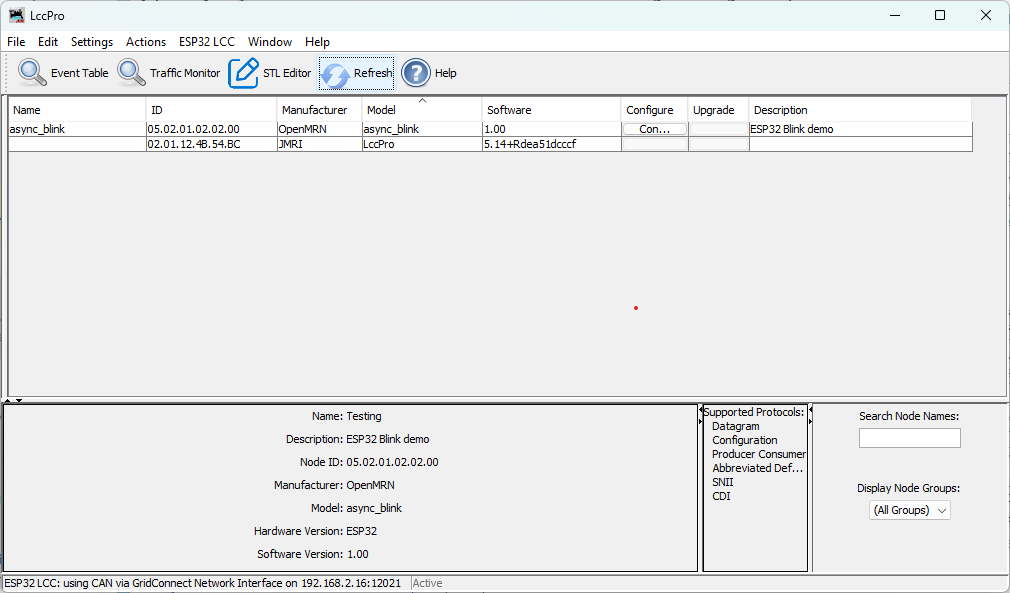

Getting Started

In the previous chapter, you learned about OpenLCB concepts: nodes, transport layers, startup sequences, and the producer/consumer event model. Now it’s time to plan your first OpenLCB node.

This chapter walks you through the key decisions we’ll make for building your node and explains the why behind each choice so you understand the trade-offs and can adapt to your own needs. (Actual implementation begins in the next chapter.)

What We’re Building

The goal of this book is to help you create an OpenLCB node—a device that can produce and consume events on an LCC network. Your node will:

- Sense inputs (buttons, switches, sensors) and produce OpenLCB events

- Control outputs (LEDs, relays, motors) by consuming OpenLCB events

- Connect to a network so other nodes can respond to your events

- Be monitored and configured via standard tools like JMRI

We’ll start with a simple example and scale to more complex scenarios in later chapters. The key concept is the pattern: once you understand how to produce and consume a single event, scaling to many inputs/outputs and adding complex logic becomes straightforward.

Progression: TCP, Then CAN, Then Full OpenMRN

We use three key technologies across this book, introduced progressively:

Phase 1: TCP/WiFi (Quick Start)

- Use WiFi/TCP transport with Arduino framework and OpenMRN-Lite library to get your first node running in minutes

- Focus on OpenLCB fundamentals (events, producers, consumers, CDI) without hardware barriers

- No CAN transceiver required—just an ESP32 and JMRI for monitoring

- Once you understand the protocol, adding CAN is straightforward

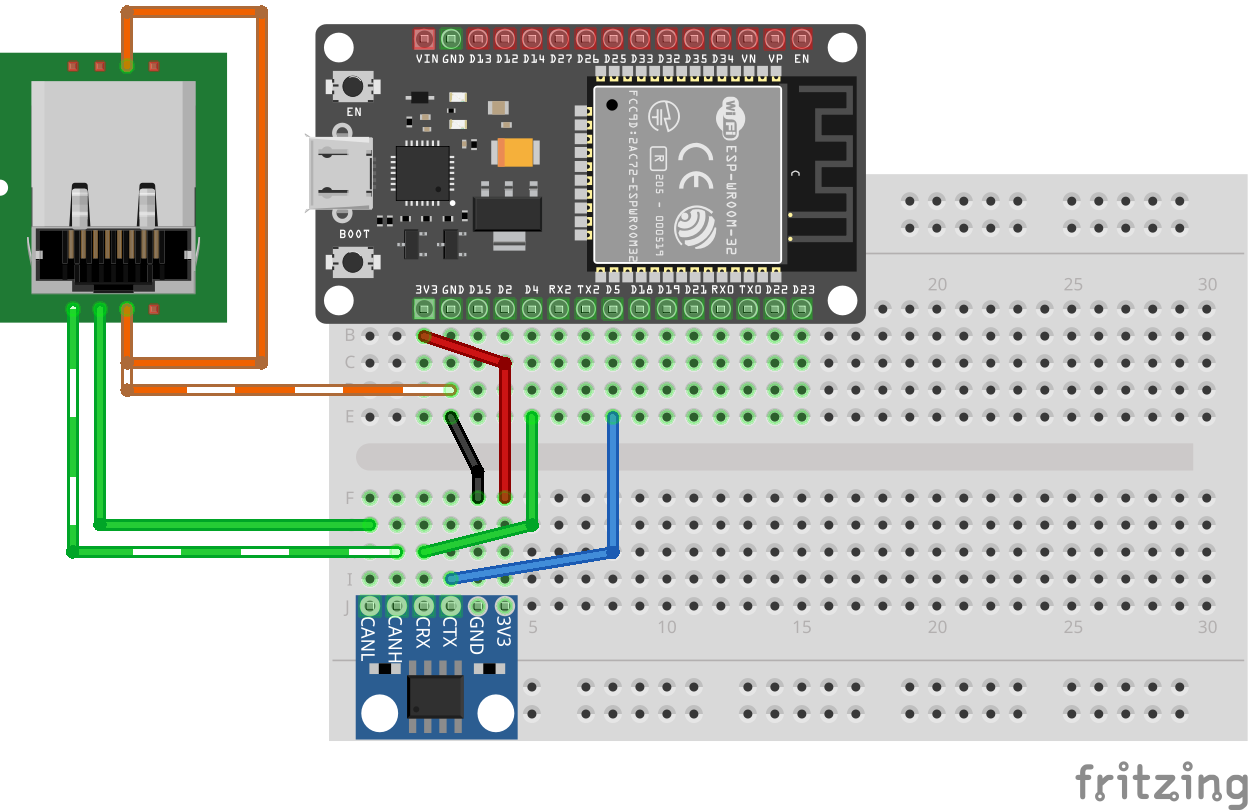

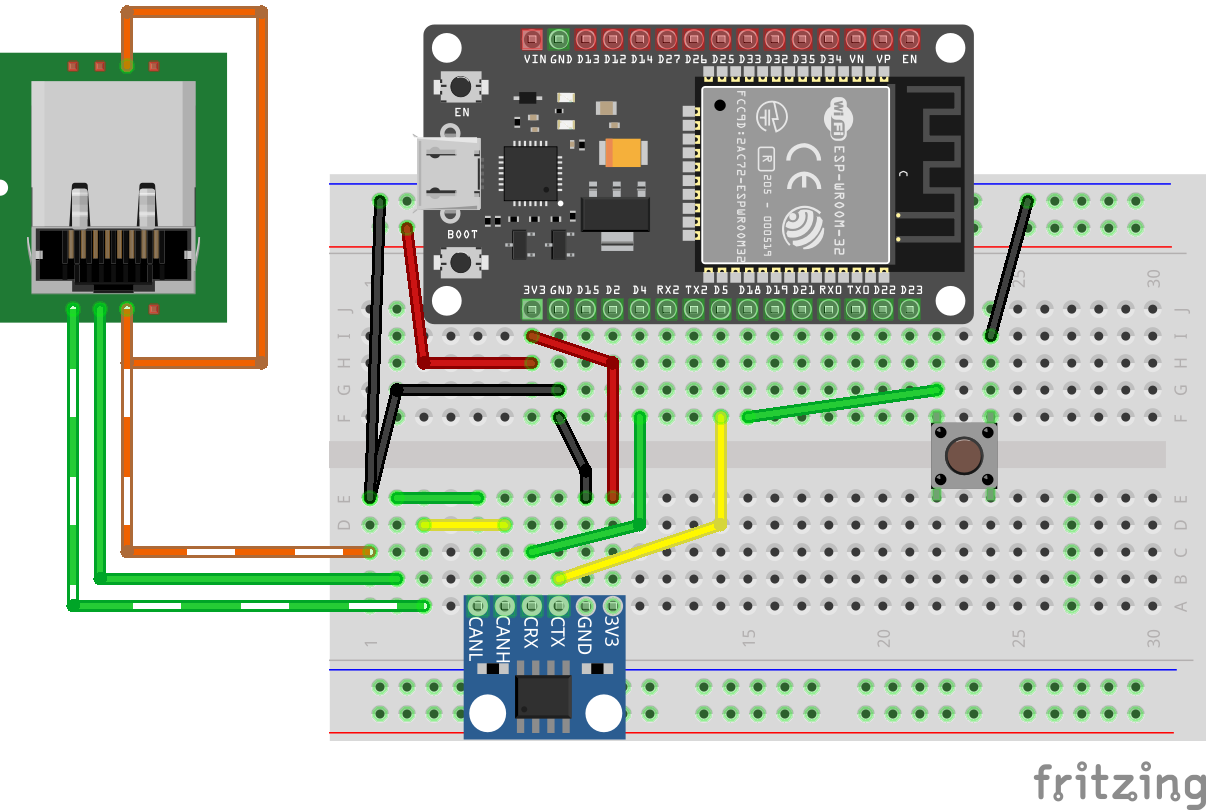

Phase 2: CAN Transport (Main Focus)

- Add a CAN transceiver (~$5) and switch from WiFi/TCP to CAN transport

- Same Arduino framework and OpenMRN-Lite library as phase 1

- Explore inputs and outputs with the real transport layer used in most LCC installations

- Build multi-node systems that communicate over CAN

- Stay here if your needs fit this model (most hobby layouts do)

Phase 3: Full OpenMRN + FreeRTOS (Advanced)

- Only if you need multi-threading, virtual nodes, or traction protocol

- Migrate from Arduino to ESP-IDF (Espressif’s full RTOS environment)

- Use full OpenMRN library with FreeRTOS threading

- Handle complex, multi-threaded scenarios (bridges, command stations, etc.)

Each phase builds on the previous one. The OpenLCB knowledge transfers directly—what changes is the platform and threading model.

Key Decisions

Building an OpenLCB node requires several key decisions, explained in the later sections of this chapter:

- Which programming framework? — Arduino for phases 1–2, FreeRTOS only if phase 3 is needed

- Which OpenLCB library? — OpenMRN-Lite (Arduino) for phases 1–2, full OpenMRN only for phase 3

- Which platform? — ESP32 (recommended), STM32, or other microcontroller

- Which IDE and build tools? — PlatformIO (recommended), Arduino IDE, or native ESP-IDF

- Which transport? — TCP/WiFi for phase 1 (quick learning), CAN for phase 2 (main focus), both for phase 3

- How do I monitor and verify? — JMRI monitoring tool, TCP hub architecture, CAN bus analysis

By the end of this chapter, you’ll understand the reasons behind each choice and why this progression makes sense for learning and building real LCC systems.

Detailed Topic Coverage

- Arduino for Early Chapters (Migration Path) — Why Arduino; how to migrate to FreeRTOS later

- OpenMRN-Lite Architecture & Capabilities — Why OpenMRN-Lite for Arduino; capabilities and limitations

- Platform: ESP32 & SPIFFS — Why ESP32; the importance of persistent storage

- Development Environments & Tooling — IDE comparison (Arduino IDE, Maker Workshop, PlatformIO); personal recommendation with GitHub Copilot

- Transports: WiFi & CAN — Why WiFi first; when to add CAN

- Monitoring & Verification — JMRI, TCP hub, GridConnect protocol

Prerequisites

Before reading further, make sure you have:

Knowledge:

- Basic embedded programming (C/C++)

- Microcontroller I/O concepts (GPIO, digital read/write)

- Familiarity with breadboards and simple circuits

- Producer/consumer model understanding (from using LCC products)

Hardware (needed for Chapter 4):

- ESP32 development board (ESP32 DevKit v1 or similar)

- USB cable for programming

- Computer with WiFi

- Optional: breadboard, jumper wires, push button, LED, resistor (for hardware integration in Chapter 5)

Software (installation covered in Chapter 4):

- VS Code or similar editor

- PlatformIO extension (or Arduino IDE / Maker Workshop)

- JMRI (for monitoring OpenLCB traffic)

If you’re missing any hardware, most items can be purchased as a kit from electronics suppliers (Adafruit, SparkFun, Amazon, AliExpress) for under $20 USD total.

What’s Next

You now have the big picture: a generic goal (inputs → events → outputs) plus the concrete stack for early chapters. Later sections in this chapter dive into each decision.

Start with Arduino for Early Chapters (Migration Path). Each section builds on the previous one, culminating in a clear understanding of our toolchain and ready-to-implement design.

By the end of this chapter, you’ll be prepared to move forward with the example implementation.

Arduino for Phases 1–2 (Migration Path for Phase 3)

The first decision in building an OpenLCB node is: which platform and framework? For phases 1–2, we use Arduino because it’s the most accessible starting point for learning and offers excellent real-world functionality. Phase 3 introduces the migration path to full FreeRTOS-based solutions only if you need advanced features.

Why Arduino First?

Arduino provides a dramatically lower learning curve and barrier to entry compared to FreeRTOS or ESP-IDF:

- Minimal setup time: You can have working code running in minutes without complex build systems or operating system knowledge

- Large ecosystem: Thousands of tutorials, libraries, and community examples

- Rapid iteration: Fast compile/upload cycle (with PlatformIO)

- Breadboard-friendly: Ideal for learning with hobby microcontrollers

- No RTOS complexity: Single-threaded execution; no threading, mutexes, or scheduler concepts needed

When learning OpenLCB, you want to focus on understanding the protocol and building real I/O functionality—not spending weeks learning RTOS concepts and debugging multi-threaded interactions. Arduino (with OpenMRN-Lite) lets you get working nodes immediately.

Arduino + OpenMRN-Lite: Phases 1–2

For phases 1–2 (TCP quick-start and CAN-based I/O), you use OpenMRN-Lite, the Arduino version of OpenMRN.

OpenMRN-Lite is production-quality and fully functional. It supports:

- CDI configuration - Configure nodes without recompiling

- CAN bus - Full CAN transport with proper arbitration

- Event producers/consumers - The core OpenLCB pattern

- Persistent storage - SPIFFS/SD card for configuration

- Real-time monitoring - JMRI integration via TCP or CAN

This is not a compromise. Most hobby and DIY LCC installations use OpenMRN-Lite for years. You’re not learning a dead-end; you’re choosing the right tool for real-world I/O projects.

Do You Need Phase 3?

Most projects stay in phases 1–2. Phase 3 (FreeRTOS + Full OpenMRN) is only for advanced scenarios:

- Command stations and bridges — Complex routing between multiple transports

- Virtual nodes — Multiple logical nodes on one device

- Traction protocol — Locomotive decoder features

- Multi-threaded hubs — Complex systems requiring background threads and advanced concurrency

If you’re building sensors, I/O controllers, or simple nodes for a layout, phases 1–2 have everything you need. Most hobby and model railroad installations never require phase 3.

If You Need Phase 3 Later

If you eventually need phase 3 features, the foundation you built in phases 1–2 makes the path forward straightforward:

- Your OpenLCB protocol knowledge transfers directly — message formats, event semantics, CDI structures all stay the same

- You’ll switch from Arduino to ESP-IDF (Espressif’s full RTOS environment) and use full OpenMRN library instead of OpenMRN-Lite

- You’ll add FreeRTOS-aware code (threading, message queues, etc.)

- The core OpenLCB concepts you’ve mastered (producers/consumers, startup sequence, events) remain unchanged—you’re adding threading sophistication on top of a solid foundation

For Phases 1–2

We’ll use Arduino + OpenMRN-Lite. This combination gives you:

- A working TCP node in minutes (phase 1)

- A fully-featured CAN node for real layouts (phase 2)

- Time to focus on OpenLCB concepts instead of RTOS complexity

- A solid foundation for phase 3 if you ever need it

Let’s get started with simplicity, solid fundamentals, and the knowledge that you can expand whenever you need to.

OpenMRN-Lite Architecture & Capabilities

You’ve learned the concepts behind OpenLCB. Now, before we write code, let’s understand the software library we’ll be using: OpenMRN-Lite. This chapter clarifies what it is, why it’s the right choice for ESP32, and what it can (and can’t) do.

What is OpenMRN-Lite?

OpenMRN-Lite is the Arduino version of OpenMRN.

This might sound like it’s a cut-down or simplified version, but that would be misleading. Instead, think of it as a version optimized for single-threaded, resource-constrained environments like Arduino and ESP32.

There are two ways to run OpenMRN code:

| Version | Threading Model | Best For | Platform |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full OpenMRN | Multi-threaded (FreeRTOS) | Complex systems, command stations, bridges | Linux, macOS, Windows, native ESP-IDF |

| OpenMRN-Lite | Single-threaded executor | Learning, sensors, simple controllers | Arduino IDE, PlatformIO (Arduino framework) on ESP32, STM32 |

The key insight: Arduino cannot run the multi-threaded version of OpenMRN. The Arduino runtime environment doesn’t provide the POSIX threading APIs that full OpenMRN requires. Therefore, OpenMRN-Lite is not a “lite” compromise—it’s the only OpenMRN version available for Arduino.

Why OpenMRN-Lite is the Right Choice for Learning OpenLCB

When building an OpenLCB node on ESP32 using Arduino, OpenMRN-Lite is the right tool for this learning path because of its simplicity and low barrier to entry.

The Alternative: You could use the full OpenMRN library with native ESP-IDF (Espressif’s real-time operating system for ESP32). This gives you access to advanced features and the full power of FreeRTOS threading. But it also requires:

- Understanding real-time operating systems, threading, and synchronization primitives

- Managing POSIX APIs and FreeRTOS queues before you even write a single OpenLCB message

- Debugging complex multi-threaded interactions

- A completely different development environment and build system

For learning OpenLCB concepts, that’s like learning to drive by starting with a race car instead of a regular car.

Why OpenMRN-Lite Instead:

- Familiar environment - Arduino’s

setup()/loop()model is straightforward and widely understood - Focus on OpenLCB - You can understand nodes, events, and producers/consumers without threading complexity

- Fast results - You’ll have working code sending real OpenLCB messages within hours

- Proven examples - The IOBoard example demonstrates CDI configuration, events, and hardware I/O patterns you can build on

- Natural progression - Once you master OpenLCB concepts, you can migrate to ESP-IDF + full OpenMRN if needed

This isn’t a permanent limitation—it’s a strategic choice that lets you learn faster and more effectively. Once you understand OpenLCB deeply, you’ll be better equipped to understand why those advanced features (virtual nodes, traction protocol, multi-threading) exist and when you might need them.

What OpenMRN-Lite DOES Support

OpenMRN-Lite has everything you need to build real, functional OpenLCB nodes:

Core Features ✅

- CDI (Configuration Description Information) - Define configuration options that JMRI can edit without recompilation

- SNIP (Simple Node Information Protocol) - Share node name and description with the network

- Event Producers & Consumers - The core OpenLCB pattern you learned in Chapter 1

- Datagrams - Reliable message delivery for configuration and data exchange

- ACDI (Abbreviated CDI) - Simpler configuration interface for basic nodes

- CAN Transport (optional) - Add a CAN transceiver to use CAN bus instead of WiFi

- TCP Hub (optional) - Connect to JMRI over WiFi using GridConnect protocol

- Factory Reset Patterns - Reset to known states without recompilation

- Persistent Configuration - Store settings in SPIFFS or SD card

The IOBoard example (the most complete OpenMRN-Lite example) demonstrates all of these features in action: CDI-based configuration, event handling, hardware I/O, and network integration. It’s exactly the pattern you’ll use when building your own nodes.

What OpenMRN-Lite Does NOT Support

There are some advanced features that require full OpenMRN with FreeRTOS threading:

What You Don’t Get ❌

- Virtual Nodes - Hosting multiple logical nodes on one microcontroller

- Traction Protocol - Command station features (throttle control, trains)

- Multi-Transport Bridging - Routing messages between CAN and TCP automatically

- Multi-Threaded I/O - Background threads for independent subsystems

- Hub Services - Virtual topology management and advanced networking

- Extensive Memory Configurations - Very large configuration systems

These features aren’t missing from OpenMRN-Lite because the developers cut corners. They’re missing because they require the threading and memory management capabilities that FreeRTOS provides, which the Arduino framework doesn’t offer.

This is not a limitation for learning OpenLCB. In fact, OpenMRN-Lite’s simplicity makes it easier to understand how OpenLCB works without being buried in threading complexity.

When to Use OpenMRN-Lite vs Full OpenMRN

Use this decision matrix to understand which tool is right for your project:

| Your Need | Use | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Learning LCC on ESP32 | OpenMRN-Lite | Single-threaded, Arduino-native, proven examples |

| Building a sensor node (button, LED, turnout) | OpenMRN-Lite | Minimal code, small footprint, stable |

| Fixed-function controller (no changes after deployment) | OpenMRN-Lite | No runtime configuration needed; extremely reliable |

| Hosting multiple nodes on one ESP32 | ❌ Not possible with Arduino | Requires FreeRTOS; switch to native ESP-IDF + full OpenMRN |

| Building a command station | ❌ Not possible with Arduino | Requires traction protocol + FreeRTOS; use Linux or dedicated hardware |

| Bridging CAN and TCP automatically | ❌ Not possible with Arduino | Requires multi-threading; use Linux |

The key takeaway: If you’re using Arduino/PlatformIO on ESP32, OpenMRN-Lite is the only OpenMRN version available. There is no “upgrade path” to full OpenMRN while staying in the Arduino ecosystem. If you need full OpenMRN features, you switch toolchains entirely (to native ESP-IDF + FreeRTOS), which requires rewriting in a different style.

Configuration & Learning Implications

One important capability worth highlighting: OpenMRN-Lite fully supports CDI, the configuration system. This means you can:

- Define configuration options in your code (node name, GPIO pins, event IDs, etc.)

- Connect to JMRI and see those options in a graphical interface

- Change configuration without recompiling or uploading new firmware

- Persist changes to the ESP32’s filesystem (SPIFFS)

This is powerful for learning because:

- You can experiment with event IDs without recompiling

- You understand how real OpenLCB nodes work (configuration happens at runtime)

- JMRI becomes a tool for monitoring and controlling your node

In this book’s v0.1, we’ll start with hardcoded configuration for simplicity. In later chapters (Chapter 5), we’ll enhance the example to use CDI configuration, showing you the pattern for building production nodes.

Looking Ahead

In Chapter 3, you’ll see how OpenMRN-Lite integrates into a real ESP32 project using Arduino and PlatformIO. The library handles all the protocol details—your job is just to define events, read inputs, and write outputs.

And if you ever do need features that OpenMRN-Lite doesn’t support, that’s okay. You’ll understand the OpenLCB concepts deeply enough to appreciate why those features exist and how they work in more complex systems. The goal of this book is to build that foundation.

Platform: ESP32 & SPIFFS

Now that we’ve committed to Arduino and OpenMRN-Lite, the next decision is: which microcontroller platform? We’ve chosen ESP32 for this book. Here’s why.

Why ESP32?

The ESP32 platform is one of the best-supported microcontrollers for OpenMRN-Lite:

Essential Features:

- Excellent Arduino support - Arduino framework is mature and stable on ESP32

- WiFi built-in - Perfect match for our WiFi/TCP transport choice (no separate shield needed)

- CAN capable - Built-in CAN controller for adding CAN hardware in future chapters

- Persistent storage (SPIFFS) - Critical for OpenMRN configuration management (more on this below)

Practical Advantages:

- Affordable - Development boards are $5–15 USD

- Powerful - Dual-core processor, plenty of memory for OpenMRNLite applications

- GPIO-rich - Enough pins for inputs, outputs, and future expansion

SPIFFS: Why It Matters

OpenMRN-Lite requires a persistent filesystem to store configuration data. When your node starts, it reads a configuration file that contains:

- Node identity (SNIP data: device name and description)

- Configuration schema definition (CDI)

- User settings (to be added in later chapters)

SPIFFS (SPI Flash File System) is ESP32’s built-in filesystem. It allows OpenMRN to:

- Store a configuration file on the device’s flash memory

- Read and update configuration without needing a separate EEPROM chip

- Persist settings across power cycles

This means:

- No external hardware required (everything is on-chip)

- You can change node name and description via JMRI without recompiling firmware

- Future configuration parameters (WiFi settings, event mappings, etc.) can be edited live

Other platforms (Arduino Mega, STM32 Nucleo boards) either lack SPIFFS or require external EEPROM components, adding complexity. ESP32 has it built-in.

Other Platforms with OpenMRN-Lite Support

OpenMRN-Lite works on other Arduino-compatible boards:

- STM32 family (Nucleo boards) via Arduino core - good option but requires external EEPROM for storage

- Arduino Mega - more memory than Uno, but no WiFi; requires WiFi shield

- Other ESP32 variants (ESP32-S3, ESP32-C3) - similar capabilities, also good choices

If you have a different board available, you can likely adapt the examples. Chapter 3 has more details on platform trade-offs. For now, ESP32 DevKit v1 is the best starting point: affordable, well-documented, and fully supported by the OpenMRN-Lite community.

Next: Choosing Your Development Environment

With platform and toolchain locked in (Arduino + OpenMRN-Lite + ESP32), the next step is choosing an IDE and build system. That’s covered in the next section.

Development Environments & Tooling

Now that you’ve decided on Arduino + OpenMRN-Lite + ESP32, you need tools to write, build, and upload code. There are three main options for Arduino development. This section compares them so you can choose what works best for you.

Three Options for Arduino Development

1. Arduino IDE

What it is: The official Arduino development environment. A simple editor with integrated build and upload tools.

Pros:

- Official and most well-documented

- Simplest setup for beginners

- Latest Arduino library support (sometimes ahead of other tools)

Cons:

- Limited editing features compared to professional IDEs

- No advanced debugging tools

- Library management can be tedious for complex projects

- Slower builds for large projects

- Limited integration with external tools (like GitHub Copilot)

2. VS Code Options — Recommended

Visual Studio Code is a powerful, modern code editor that supports Arduino development through extensions. Unlike the Arduino IDE, VS Code gives you professional editing features, integrations, and an extensive ecosystem of tools—all in one environment. This significantly improves your development experience.

Benefits of VS Code for Arduino Development:

- Professional editor experience - syntax highlighting, code formatting, IntelliSense, and multi-file navigation

- GitHub Copilot integration - AI-assisted code completion, documentation generation, and debugging suggestions

- Extensible ecosystem - seamless access to Git, terminal, testing tools, debugging, and thousands of extensions

- Faster development workflow - superior editing and navigation compared to Arduino IDE

There are two main extensions available for Arduino development in VS Code:

2A. Arduino Maker Workshop (VS Code Extension)

What it is: An extension that brings the Arduino CLI directly into VS Code, giving you the same capabilities as the official Arduino IDE.

Pros:

- Full Arduino CLI capability - identical board and library support as the official Arduino IDE; no loss of functionality

- Good library management - same library ecosystem as Arduino IDE

Cons:

- Smaller community than PlatformIO

- May have minor library update lag compared to official Arduino IDE (rarely an issue in practice)

2B. PlatformIO (VS Code Extension)

What it is: A professional-grade build system and IDE extension specifically designed for embedded development across multiple platforms.

Pros:

- Fastest builds - significantly faster than Arduino IDE or Maker Workshop

- Professional features - library version pinning, dependency resolution, build system profiling

- Strong community - large ecosystem of libraries and examples

- Non-Arduino platform support - extends beyond Arduino boards to ESP-IDF, FreeRTOS, STM32, and hundreds of other embedded platforms; supports phase 3 migration to full OpenMRN

Cons:

- Latest Arduino library versions sometimes lag by 1–2 releases (minor issue in practice)

- Slightly steeper learning curve than Arduino IDE

- More configuration options (which is a pro for power users)

Personal Recommendation: PlatformIO + VS Code + GitHub Copilot

I personally use PlatformIO in VS Code with GitHub Copilot (paid subscription) enabled. Here’s why:

- Professional environment - PlatformIO’s build system is industrial-strength; you’re learning with real tools you’d use in production.

- GitHub Copilot - The entry-level paid subscription (~$10/month) is exceptional value. Copilot goes way beyond auto-completion; I use it to write and edit actual code. This dramatically lowers the barrier to entry and makes you far more productive:

- Writing functions and complex logic from natural language descriptions

- Refactoring and improving existing code

- Generating unit tests and helper functions

- Explaining unfamiliar code and OpenMRN APIs

- Fast iteration - PlatformIO’s build speed means less waiting between code changes and testing.

- Future flexibility - If you later migrate to full OpenMRN, PlatformIO supports it seamlessly.

The Copilot subscription is worth the investment if you’re doing this seriously. It’s not a necessity—you can learn OpenLCB without it—but it significantly improves the learning experience and accessibility for hobbyists.

Choosing Your Own Path

Each option is valid:

- Lowest barrier to entry? → Arduino IDE

- VS Code + Arduino CLI? → Arduino Maker Workshop

- Professional, fastest, future-proof? → PlatformIO

This book includes detailed setup instructions for PlatformIO (Chapter 3). If you prefer a different option, the concepts apply equally; you’ll just follow that tool’s documentation for the build and upload steps.

Transports: WiFi/TCP and CAN

OpenLCB is designed to work over different physical transports. We use two main options across this book: WiFi/TCP (for rapid learning) and CAN (for real-world deployments).

Phase 1: WiFi/TCP Transport (Quick Start)

We begin with WiFi and TCP to get your first OpenLCB node running in minutes:

For Rapid Learning:

- No special hardware required - ESP32 boards have WiFi built-in; no CAN transceivers needed

- Easy monitoring - Standard network tools and JMRI can capture all traffic

- Faster iteration - Wireless upload and debugging without physical bus connections

- Focus on protocol - Understand events, producers, and consumers without hardware distractions

Key Insight: The OpenLCB message formats, node startup, and event handling work identically over WiFi/TCP and CAN. Everything you learn in phase 1 transfers directly to CAN-based implementations in phase 2. TCP is a deliberate stepping stone, not a dead-end.

Phase 2: CAN Bus Transport (Main Focus)

CAN (Controller Area Network) is the traditional transport for OpenLCB and is used in the vast majority of commercial LCC products. After mastering the protocol over TCP, you’ll add CAN hardware and use it as your primary transport.

Why CAN is the Real-World Standard:

- Excellent noise immunity - designed for harsh environments (layout with motors, lights, switching supplies)

- Built-in collision handling - arbitration is hardware-enforced, not software-managed

- Two-wire bus - simple termination (120Ω at both ends)

- Industry-proven - decades of use in automotive and industrial settings

- Multi-device scalability - hundreds of nodes can share the same two-wire bus

- Compatibility - interoperability with commercial LCC products and installations

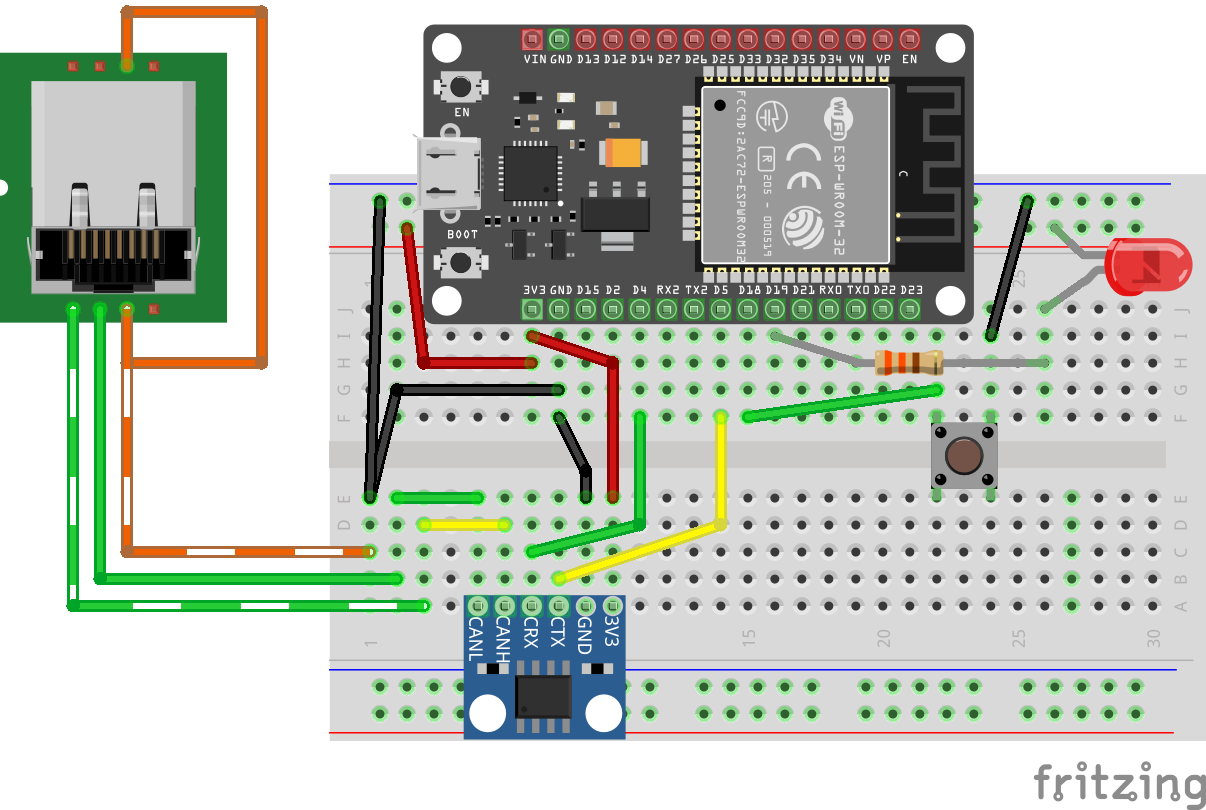

What You’ll Add:

- A CAN transceiver board (~$5)

- Proper bus termination (two 120Ω resistors)

- A two-wire connection to other nodes

When Phase 2 Starts: Chapters on inputs and outputs focus on CAN. You’ll explore multi-node systems, real-world layouts, and the patterns used in most model railroad installations.

Phase 3: Multi-Transport Integration (Advanced)

Once you’ve mastered CAN-based I/O, you may eventually need to:

- Bridge TCP and CAN on the same device

- Implement virtual nodes

- Use the traction protocol for command stations

These advanced features require full OpenMRN with FreeRTOS threading, covered in later chapters.

The Progression

This is one of OpenLCB’s strengths: the protocol is transport-agnostic. You can:

- Start with WiFi/TCP on your workbench (phase 1—no special hardware)

- Learn OpenLCB fundamentals (events, producers, consumers, CDI)

- Add CAN hardware and switch to phase 2 (same code patterns; now using the real transport)

- Integrate both transports if needed (phase 3, only when necessary)

The key insight: learning with TCP doesn’t waste your time. It’s a deliberate stepping stone that lets you focus on protocol before worrying about hardware. When you move to CAN, the only change is the physical connection and a few hardware initialization lines—your OpenLCB knowledge applies perfectly.

Monitoring & Verification

Building an OpenLCB node is only half the battle. You also need visibility into what your node is doing. This section introduces the monitoring tools and how to verify your node is working correctly.

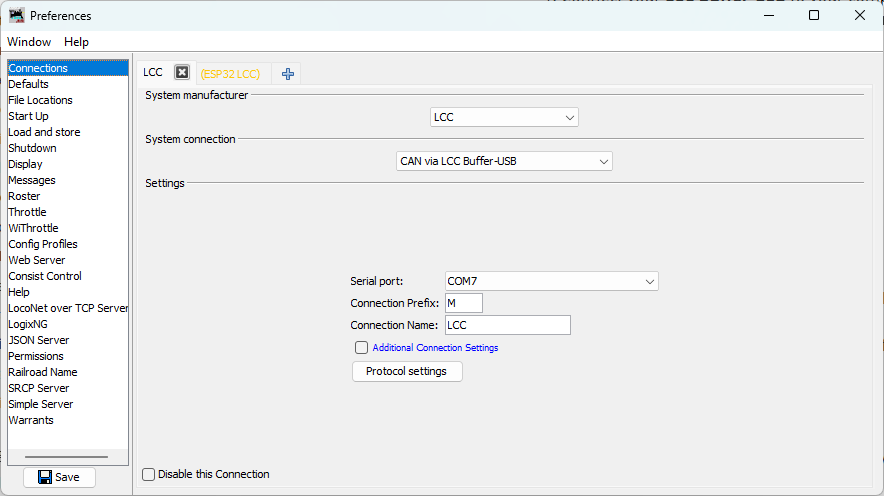

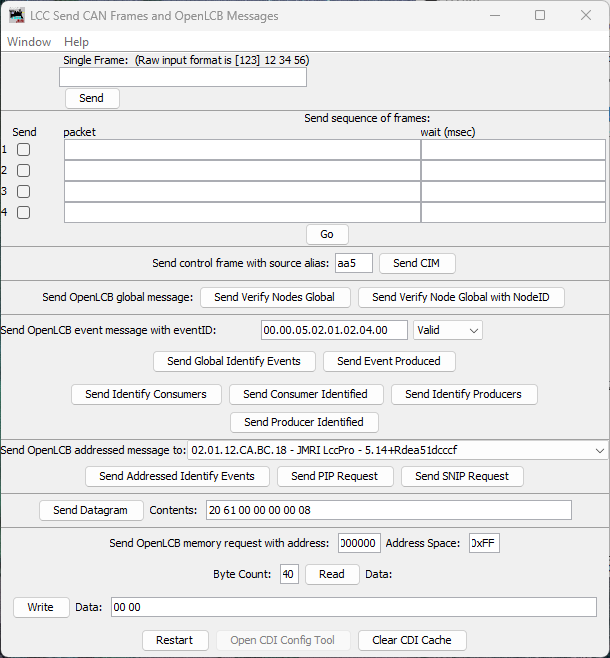

JMRI: The Essential Monitoring Tool

JMRI (Java Model Railroad Interface) is a free, open-source tool for model railroad control and monitoring. It’s essential for OpenLCB development:

Why JMRI?

- Message decoder - Translates raw hex into readable OpenLCB messages

- Network monitor - See all CID, RID, AMD, event messages in real-time

- Testing tool - Send events to your node and verify responses

- Layout integration - Connect your node to a larger LCC network

- Configuration editor - Edit node settings (via CDI) without recompiling firmware

For OpenLCB development, JMRI is invaluable for seeing what’s happening on the network.

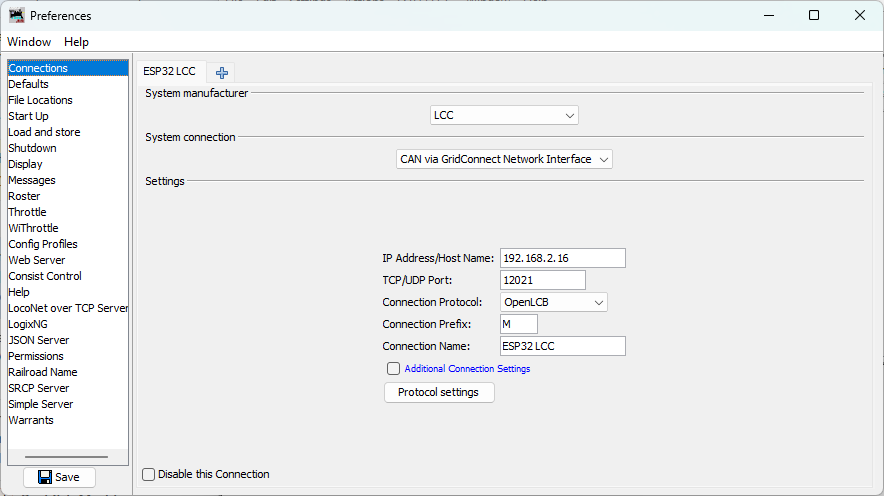

TCP/GridConnect Protocol

When your ESP32 node runs a TCP server (on port 12021 by default), JMRI connects as a TCP client. The communication uses GridConnect ASCII format, which is human-readable:

:X18AD4000N;

:X19B84000N;

:X1CED4000N;

:X1080C000N;

Each line is an OpenLCB message. The format is:

:X- GridConnect header18AD4000- OpenLCB header and data (hex)N- Indicates normal message (not error);- Message terminator

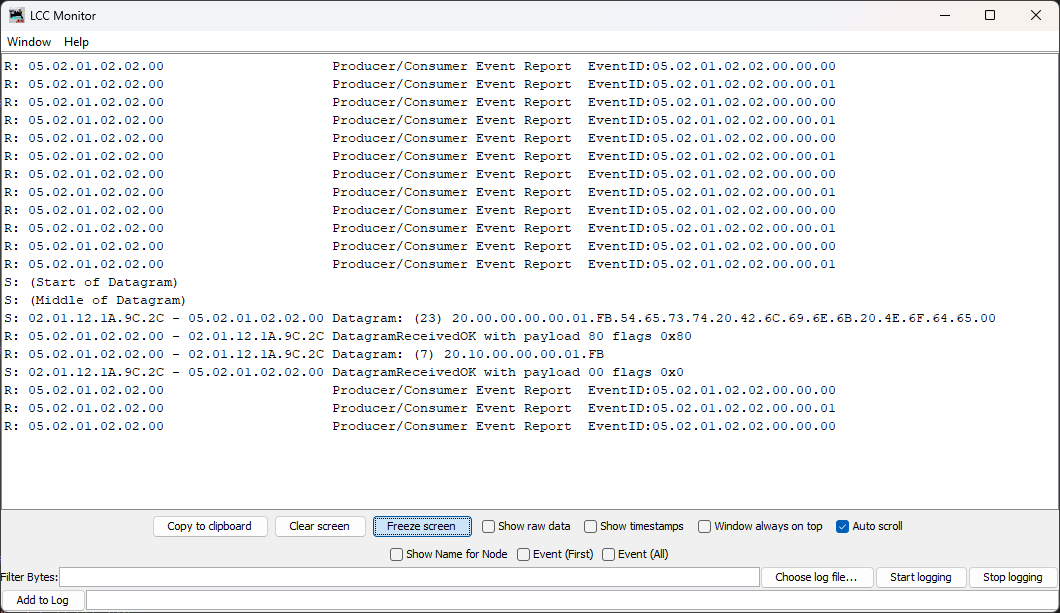

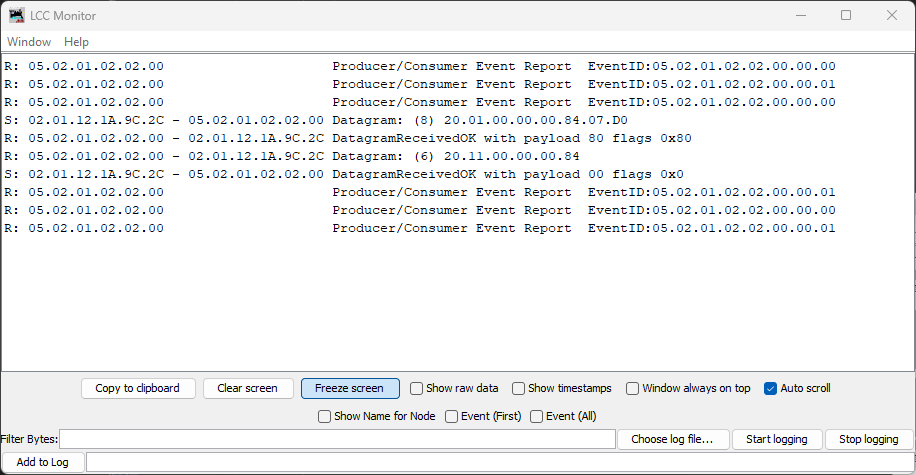

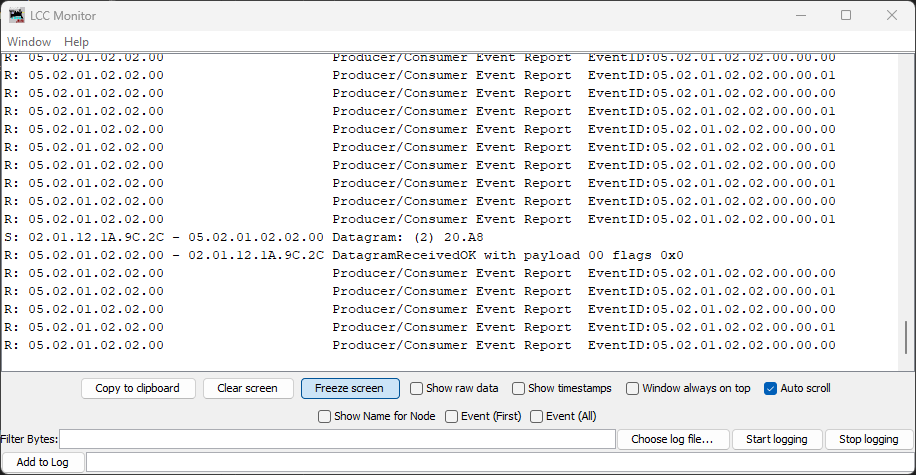

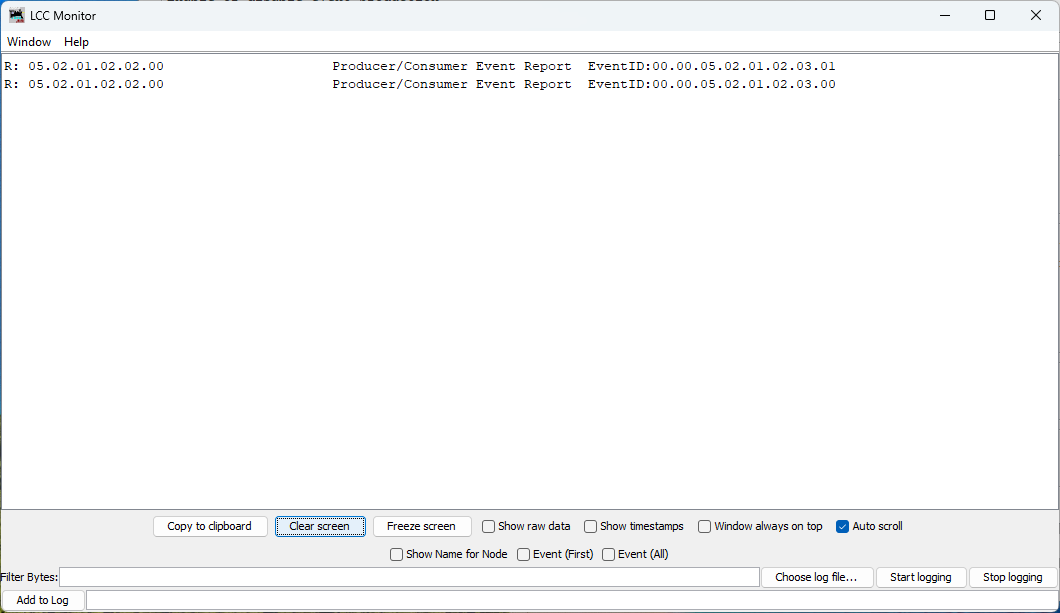

What You’ll See: When your node starts up, JMRI shows:

- Four CID frames (checking alias availability)

- RID frame (reserving an alias)

- AMD frame (mapping Node ID to alias)

- Initialized message (node is online and ready)

- Producer/Consumer Identified messages (node capabilities)

- Event reports (button presses, LED changes, etc.)

This startup sequence takes a few milliseconds and happens automatically.

Running a Local TCP Hub

Your ESP32 node runs both a node (producing/consuming events) and a hub (routing messages) simultaneously. The hub is a simple TCP server:

- Listens on port 12021 by default

- Accepts connections from JMRI, other nodes, and monitoring tools

- Forwards all OpenLCB messages between participants

- Requires just a few lines of OpenMRN-Lite code to set up

This is a key design pattern: a single device can be both a node and a hub, which is perfect for development and small layouts.

Quick Verification Steps

When your node is running:

- Serial monitor - See startup messages and debug output

- JMRI connection - Connect JMRI to

localhost:12021(or your ESP32’s IP address) - Message trace - Watch the four startup frames (CID/RID/AMD/Init)

- Event test - Produce and consume a test event; watch it appear in JMRI

- Node properties - View your node’s name and description (from SNIP data)

Chapter 4 includes detailed screenshots and step-by-step JMRI configuration instructions.

What’s Next

With monitoring tools in place, you’re ready to:

- Install PlatformIO (Chapter 3)

- Build and deploy the async_blink example

- Verify it with JMRI

- Start understanding the code

Let’s get hands-on in the next chapter.

Your First WiFi-Based OpenLCB Node

This chapter covers everything needed to build and deploy your first OpenLCB node on an ESP32 microcontroller using Arduino and PlatformIO, connected via WiFi.

Overview

The ESP32 is a powerful, affordable microcontroller with built-in WiFi connectivity, making it ideal for learning OpenLCB concepts. This chapter walks through building a working OpenLCB node that simultaneously runs the node protocol stack and hosts a TCP Hub—allowing JMRI to monitor and control your WiFi-connected node over a network.

Unlike “real” OpenLCB networks (which typically use CAN hardware transport), this WiFi-based approach lets you get a functioning node running quickly without special hardware, and it’s perfect for embedded systems with network connectivity.

As described in the “Network Architecture” section of Chapter 2, your ESP32 will act as both:

- An OpenLCB node that produces and consumes events

- A TCP Hub listening on port 12021 for JMRI connections

We’ll be using the OpenMRN-Lite library, which is the Arduino version of OpenMRN. If you’re curious about why OpenMRN-Lite specifically, or what it can (and can’t) do, see Chapter 2.2 (“OpenMRN-Lite Architecture & Capabilities”) for a deeper dive. For now, know that it’s the right tool for the job and it has everything we need to build real, functional OpenLCB nodes.

Board Selection

ESP32 Board Selection

Before installing software, you’ll want to order an ESP32 development board. This section helps you choose the right board for this tutorial.

The ESP32 family includes many board variants. For this tutorial, we recommend boards with sufficient GPIO pins, USB programming support, and built-in CAN capability for future chapters.

Recommended Board: ESP32 DevKit V1

ESP32 DevKit V1 / ESP32-WROOM-32 (Xtensa architecture)

- Most common and affordable ESP32 development board

- 30+ GPIO pins available (plenty for expansion)

- Built-in USB-to-serial converter (CP2102 or CH340)

- 4MB flash memory (sufficient for OpenMRNLite applications)

- Built-in CAN controller (TWAI) for future CAN chapters

- Best OpenMRNLite compatibility - fully tested and supported

- Available from multiple manufacturers (Espressif, DOIT, etc.)

- Cost: $5-10 USD

This is the board we’ll use throughout the tutorial.

Alternative Boards

ESP32-DevKitC

- Official Espressif development board

- Similar pinout to DevKit V1

- Excellent documentation and support

- Slightly more expensive but guaranteed quality

ESP32-S3 (Xtensa architecture)

- Newer variant with USB-OTG support

- More memory and GPIO options

- Built-in CAN controller

- Good OpenMRNLite support

Boards to Avoid (for now)

ESP32-C3 (RISC-V architecture)

- Different CPU architecture (RISC-V vs Xtensa)

- OpenMRNLite has compatibility issues with ESP32-C3

- Missing required ESP-IDF headers in Arduino framework

- Wait for future OpenMRNLite updates before using

What You Need Now

To get started with the software-only version:

- Just the ESP32 board with USB cable

For the hardware integration phase (optional, later):

- Solderless breadboard

- Tactile pushbutton

- LED (any color)

- 220Ω resistor

- Jumper wires

Purchasing

ESP32 boards are available from:

- Amazon / eBay: Search “ESP32 DevKit” (verify reviews)

- AliExpress / Banggood: Direct from manufacturers (longer shipping)

- Adafruit / SparkFun: Higher quality, better support, higher cost

- DigiKey / Mouser: For bulk or commercial projects

Order your board now, then continue with the software setup while you wait for delivery.

Development Setup

PlatformIO Installation & Setup

PlatformIO is a professional embedded development platform that provides a unified build system, library management, and debugging tools. It integrates with VS Code to create a powerful development environment.

Installing VS Code

If you don’t already have Visual Studio Code installed:

- Download VS Code from code.visualstudio.com

- Run the installer for your operating system (Windows, macOS, or Linux)

- Follow the installation wizard with default options

- Launch VS Code after installation completes

Installing PlatformIO Extension

- Open VS Code

- Click the Extensions icon in the left sidebar (or press

Ctrl+Shift+X/Cmd+Shift+X) - Search for “PlatformIO IDE”

- Click Install on the “PlatformIO IDE” extension by PlatformIO

- Wait for the installation to complete (this may take several minutes as it downloads toolchains)

- Restart VS Code when prompted

After restarting, you should see a new PlatformIO icon (alien head) in the left sidebar.

Note: The ESP32 platform and toolchain will be installed automatically when you create your first project. PlatformIO handles all the toolchain downloads and configuration for you.

Project Structure

Creating Your First Project: async_blink_esp32

Now we’ll create the actual project we’ll be working with throughout this chapter. Instead of creating a throwaway test project, we’ll jump straight into building our OpenLCB node.

Create the Project

- Click the PlatformIO icon in the left sidebar

- Select New Project from Quick Access

- Enter project name: async_blink_esp32

- For Board, search and select DOIT ESP32 DEVKIT V1 (or

esp32doit-devkit-v1) - Framework should automatically select Arduino

- Click Finish

PlatformIO will:

- Create the project structure

- Download the ESP32 platform and toolchain (first time only, may take several minutes)

- Set up the Arduino framework

- Create a basic

src/main.cppfile

Understanding the Project Structure

After creation, you’ll see this structure:

async_blink_esp32/

├── platformio.ini # Project configuration

├── src/

│ └── main.cpp # Your application code (we'll replace this)

├── lib/ # Project-specific libraries

├── include/ # Header files

└── test/ # Unit tests (optional)

The platformio.ini file should look like this:

[env:esp32doit-devkit-v1]

platform = espressif32@6.12.0

board = esp32doit-devkit-v1

framework = arduino

monitor_speed = 115200

Adding OpenMRNLite to Your Project

OpenMRNLite is the lightweight version of OpenMRN designed for Arduino-compatible platforms. It provides all the core LCC/OpenLCB functionality without the full complexity of the OpenMRN framework.

Installation via platformio.ini

Open the platformio.ini file in your async_blink_esp32 project and add OpenMRNLite to the library dependencies:

[env:esp32doit-devkit-v1]

platform = espressif32@6.12.0

board = esp32doit-devkit-v1

framework = arduino

lib_deps = openmrn/OpenMRNLite@2.0.0

monitor_speed = 115200

Save the file. That’s it! PlatformIO will automatically download OpenMRNLite from the registry when you build the project.

About OpenMRNLite version 2.0.0: We’re using v2.0.0 rather than newer versions because:

- Version 2.0.0 is fully compatible with PlatformIO’s current ESP32 platform

- Later versions (2.2.x+) require newer ESP-IDF features not yet available in PlatformIO

- All core OpenLCB functionality is present in v2.0.0

About monitor_speed: This setting ensures the serial monitor uses 115200 baud, matching the Serial.begin(115200) call in our code. Without this, you’ll see garbled output instead of readable text.

About platform versions and Arduino-ESP32

Arduino-ESP32 has two major versions: 2.x and 3.x. The Arduino IDE now supports 3.x, but PlatformIO still uses 2.x. The

platform = espressif32@6.12.0pins us to PlatformIO’s current 2.x series.Why not upgrade to Arduino-ESP32 3.x?

- Arduino-ESP32 3.x is still evolving with breaking changes to the build system, partition handling, WiFi stack, and more.

- PlatformIO prioritizes stability over bleeding-edge features. They thoroughly test each framework version across hundreds of boards, toolchains, and debuggers before releasing.

- Smaller maintenance burden: By using a tested, stable version, we reduce variables when troubleshooting issues.

OpenMRNLite v2.0.0 is designed for the Arduino-ESP32 2.x that PlatformIO provides via espressif32@6.12.0. You’re trading bleeding-edge features for rock-solid reliability, which is perfect for learning OpenLCB fundamentals.

Note: The code in this chapter should also work with Arduino-ESP32 3.x using either the Arduino IDE or Arduino Maker Workshop, but we haven’t tested those configurations.

Verification

Let’s verify everything is working by building the project:

-

In VS Code, click the PlatformIO icon in the left sidebar

-

Under PROJECT TASKS → esp32doit-devkit-v1, click Build

-

PlatformIO will:

- Download OpenMRNLite (first time only)

- Compile the default

main.cpp - Display build output

-

Look for SUCCESS at the end of the output

Note: The first build will take longer as PlatformIO downloads the library and compiles it. Subsequent builds are much faster.

If the build succeeds, OpenMRNLite is installed correctly and you’re ready to write code!

Adding Config.h

Code Configuration

Now we’ll create the actual OpenLCB node that produces alternating events. This demonstrates the core OpenLCB protocol behavior you learned in Chapter 1 (node initialization and event production) without requiring physical hardware.

Creating the Configuration Header

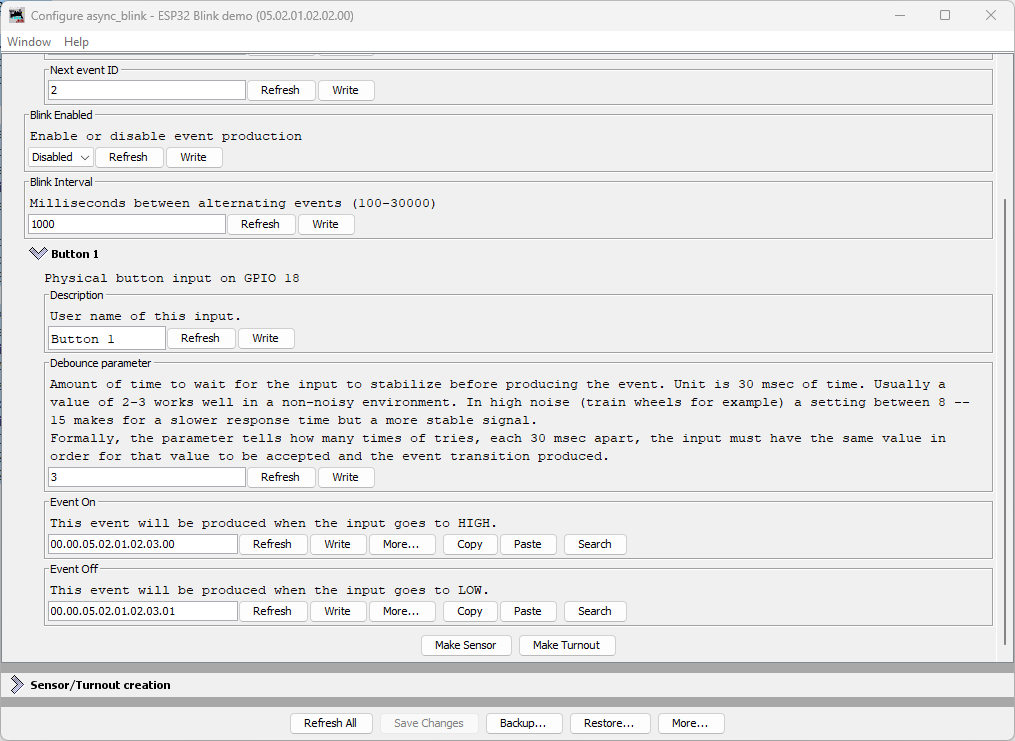

OpenMRNLite requires a configuration structure (CDI - Configuration Description Information) even for simple nodes. We’ll create a minimal config.h file.

Create the file include/config.h with this content:

#ifndef _ASYNC_BLINK_CONFIG_H_

#define _ASYNC_BLINK_CONFIG_H_

#include "openlcb/ConfigRepresentation.hxx"

#include "openlcb/MemoryConfig.hxx"

namespace openlcb {

/// SNIP Static Data - Manufacturer information (read-only, compiled into firmware)

extern const SimpleNodeStaticValues SNIP_STATIC_DATA = {

4, // Version

"OpenMRN", // Manufacturer

"async_blink", // Model

"ESP32", // Hardware version

"1.00" // Software version

};

/// SNIP Dynamic Data - User-editable node name and description

/// These are stored in the config file and can be read/written via JMRI

static const char SNIP_NODE_NAME[] = "async_blink";

static const char SNIP_NODE_DESC[] = "ESP32 Blink demo";

/// Version number for the configuration structure

static constexpr uint16_t CANONICAL_VERSION = 0x0001;

/// Minimal configuration segment with just internal config

CDI_GROUP(AsyncBlinkSegment, Segment(MemoryConfigDefs::SPACE_CONFIG), Offset(128));

CDI_GROUP_ENTRY(internal_config, InternalConfigData);

CDI_GROUP_END();

/// The main CDI structure

CDI_GROUP(ConfigDef, MainCdi());

CDI_GROUP_ENTRY(ident, Identification);

CDI_GROUP_ENTRY(acdi, Acdi);

CDI_GROUP_ENTRY(userinfo, UserInfoSegment, Name("User Info"));

CDI_GROUP_ENTRY(seg, AsyncBlinkSegment, Name("Settings"));

CDI_GROUP_END();

} // namespace openlcb

#endif // _ASYNC_BLINK_CONFIG_H_

What this does: Defines the CDI (Configuration Description Information) structure that OpenMRNLite uses to expose node configuration to JMRI. The configuration includes:

- SNIP Static Data: Read-only manufacturer, model, and version information (compiled into firmware)

- SNIP Dynamic Data: User-editable node name and description stored in the config file (visible in JMRI node properties)

- Acdi and UserInfo: Standard OpenLCB configuration segments

- AsyncBlinkSegment: Internal configuration area for this node (currently minimal, but available for future expansion)

Configuration Storage: Configuration is saved to SPIFFS on first boot (via

factory_reset()shown in the next section) and persists across restarts. In v0.1, the initial configuration is hardcoded in the constants above. See the next chapter “Configuration & Persistence” (Chapter 4) to understand how configuration storage works, how to edit settings via JMRI, and howapply_configuration()fits into the lifecycle.

Updating Main.cpp

Code Implementation

The Complete Main Code

Now replace the contents of src/main.cpp with the following code:

/** \copyright

* Copyright (c) 2024, OpenLCB Technical Introduction

* All rights reserved.

*

* Example code for educational purposes demonstrating OpenLCB node startup

* and event handling on ESP32 using WiFi/TCP transport.

*

* \file main.cpp

*

* Simple async_blink example for ESP32 with WiFi - produces two alternating

* events every second, demonstrating OpenLCB node initialization and event

* production without requiring physical GPIO hardware.

*/

#include <Arduino.h>

#include <WiFi.h>

#include <SPIFFS.h>

#include <OpenMRNLite.h>

#include "utils/GcTcpHub.hxx"

#include "config.h"

// WiFi credentials - CHANGE THESE to match your network

const char* ssid = "YourWiFiSSID";

const char* password = "YourWiFiPassword";

// OpenLCB Node ID - must be unique on your network

// This ID is in the reserved range for experimental use

static constexpr uint64_t NODE_ID = 0x050201020200ULL;

// Event IDs that will be alternated

// These match the desktop async_blink example

static const uint64_t EVENT_ID_0 = 0x0502010202000000ULL;

static const uint64_t EVENT_ID_1 = 0x0502010202000001ULL;

// Create the OpenMRN stack object

OpenMRN openmrn(NODE_ID);

// TCP Hub for JMRI connectivity

GcTcpHub* tcp_hub = nullptr;

// ConfigDef comes from config.h and defines the configuration layout

static constexpr openlcb::ConfigDef cfg(0);

// OpenLCB configuration - required by OpenMRNLite

namespace openlcb {

// Name of CDI.xml to generate dynamically

const char CDI_FILENAME[] = "/spiffs/cdi.xml";

// This will stop openlcb from exporting the CDI memory space upon start

const char CDI_DATA[] = "";

// Path to the config file and its size

const char* const CONFIG_FILENAME = "/spiffs/openlcb_config";

const size_t CONFIG_FILE_SIZE = cfg.seg().size() + cfg.seg().offset();

// SNIP (Simple Node Information Protocol) dynamic data storage

const char* const SNIP_DYNAMIC_FILENAME = CONFIG_FILENAME;

}

// State variable to track which event to send

bool event_state = false;

// Timing for event production (1 second = 1000 milliseconds)

unsigned long last_event_time = 0;

const unsigned long EVENT_INTERVAL = 1000;

/**

* Configuration update listener for factory reset and config persistence.

*

* factory_reset() is called automatically by OpenMRN on first boot (when the

* config file doesn't exist yet). It initializes SNIP dynamic data (node name

* and description) which is then saved to SPIFFS and persists across restarts.

*

* apply_configuration() is called when the user modifies configuration through

* JMRI (or other LCC tools). In v0.1, it returns UPDATED without doing anything.

* In Chapter 5, we'll implement actual config persistence when this is called.

*/

class FactoryResetHelper : public DefaultConfigUpdateListener

{

public:

UpdateAction apply_configuration(int fd, bool initial_load,

BarrierNotifiable *done) OVERRIDE

{

AutoNotify n(done);

// In v0.1, we don't handle runtime config changes yet.

// Real nodes would persist changes here when the user modifies

// configuration through JMRI. See Chapter 5 for implementation.

return UPDATED;

}

void factory_reset(int fd) override

{

// Called on first boot to initialize the configuration file.

// Write initial SNIP dynamic data (node name and description).

// This data is then saved to SPIFFS and is displayed by JMRI

// in the node properties dialog.

cfg.userinfo().name().write(fd, openlcb::SNIP_NODE_NAME);

cfg.userinfo().description().write(fd, openlcb::SNIP_NODE_DESC);

}

} factory_reset_helper;

/**

* Initialize Serial communication and print startup banner.

*/

void init_serial() {

Serial.begin(115200);

delay(500); // Give serial time to initialize

Serial.println("\n\n=== OpenLCB async_blink ESP32 Example ===");

Serial.printf("Node ID: 0x%012llX\n", NODE_ID);

Serial.printf("Event 0: 0x%016llX\n", EVENT_ID_0);

Serial.printf("Event 1: 0x%016llX\n", EVENT_ID_1);

}

/**

* Initialize SPIFFS filesystem for configuration storage.

*/

void init_filesystem() {

Serial.println("\nInitializing SPIFFS...");

if (!SPIFFS.begin(true)) { // true = format if mount fails

Serial.println("SPIFFS mount failed! Halting.");

while (1) { delay(1000); } // Stop here if filesystem fails

}

Serial.println("SPIFFS initialized successfully");

}

/**

* Connect to WiFi network.

*/

void init_network() {

Serial.printf("\nConnecting to WiFi SSID: %s\n", ssid);

WiFi.begin(ssid, password);

// Wait for WiFi connection

while (WiFi.status() != WL_CONNECTED) {

delay(500);

Serial.print(".");

}

Serial.println("\nWiFi connected!");

Serial.printf("IP Address: %s\n", WiFi.localIP().toString().c_str());

}

/**

* Initialize OpenMRN stack and configuration.

* This creates the config file and starts the stack.

* FactoryResetHelper automatically initializes SNIP data on first boot.

*/

void init_openlcb_stack() {

// Create the CDI.xml dynamically

// CDI describes what configuration options are available

Serial.println("\nCreating CDI configuration descriptor...");

openmrn.create_config_descriptor_xml(cfg, openlcb::CDI_FILENAME);

// Create the config file if it doesn't exist

// OpenMRNLite requires this even for simple nodes

Serial.println("Initializing OpenLCB configuration...");

openmrn.stack()->create_config_file_if_needed(cfg.seg().internal_config(),

openlcb::CANONICAL_VERSION,

openlcb::CONFIG_FILE_SIZE);

// Start the OpenMRN stack

// This initiates the OpenLCB node initialization sequence:

// 1. Check ID (CID) - verifies Node ID is unique

// 2. Reserve ID (RID) - claims the Node ID

// 3. Announce Membership (AMD) - announces node to network

// 4. Initialization Complete - node enters normal operation

Serial.println("\nStarting OpenLCB stack...");

openmrn.begin();

// Start the executor thread for background processing

// REQUIRED for TCP Hub to accept connections

Serial.println("Starting executor thread...");

openmrn.start_executor_thread();

}

/**

* Initialize TCP Hub for JMRI connectivity.

*/

void init_tcp_hub() {

Serial.println("Starting TCP Hub on port 12021...");

tcp_hub = new GcTcpHub(

openmrn.stack()->can_hub(), // Reference to the CAN hub

12021 // TCP port (standard for OpenLCB)

);

Serial.println("TCP Hub listening. JMRI can connect to this device on port 12021");

}

/**

* Arduino setup() - runs once at startup

*

* This function initializes all hardware and software subsystems:

* 1. Serial communication

* 2. SPIFFS filesystem

* 3. WiFi network

* 4. OpenMRN stack

* 5. TCP Hub for JMRI connectivity

*/

void setup() {

init_serial();

init_filesystem();

init_network();

init_openlcb_stack();

init_tcp_hub();

Serial.println("OpenLCB node initialization complete!");

Serial.println("Entering run mode - will alternate events every 1 second\n");

// Record start time for event production

last_event_time = millis();

}

/**

* Arduino loop() - runs continuously

*

* This function:

* 1. Calls openmrn.loop() to process OpenLCB protocol messages

* 2. Alternates between two events every second

* 3. Prints event production to serial monitor

*/

void loop() {

// CRITICAL: Must call openmrn.loop() frequently to process messages

openmrn.loop();

// Check if it's time to produce an event (every 1 second)

unsigned long current_time = millis();

if (current_time - last_event_time >= EVENT_INTERVAL) {

// Alternate event state

event_state = !event_state;

// Send the event

uint64_t event_to_send = event_state ? EVENT_ID_1 : EVENT_ID_0;

openmrn.stack()->executor()->add(new CallbackExecutable([event_to_send]() {

openmrn.stack()->send_event(event_to_send);

}));

// Print to serial monitor

Serial.printf("Produced event: 0x%016llX (state: %d)\n",

event_to_send, event_state ? 1 : 0);

// Update timing

last_event_time = current_time;

}

}

Before You Build

Update WiFi credentials in the code! The build will succeed even with placeholder credentials, but the ESP32 won’t connect to WiFi when you upload it.

Important: Never check WiFi credentials (or any secrets) into a version control repository. In a real project, use environment variables or a separate configuration file excluded from git.

Better approach: OpenMRNLite provides

Esp32WiFiManagerfor a more robust WiFi configuration system, but we’re using hardcoded credentials here for simplicity in this learning example.

Future note: WiFi is temporary for learning. When we add CAN transport in a later chapter, we’ll remove the WiFi code entirely. This approach helps you understand the differences between transport types.

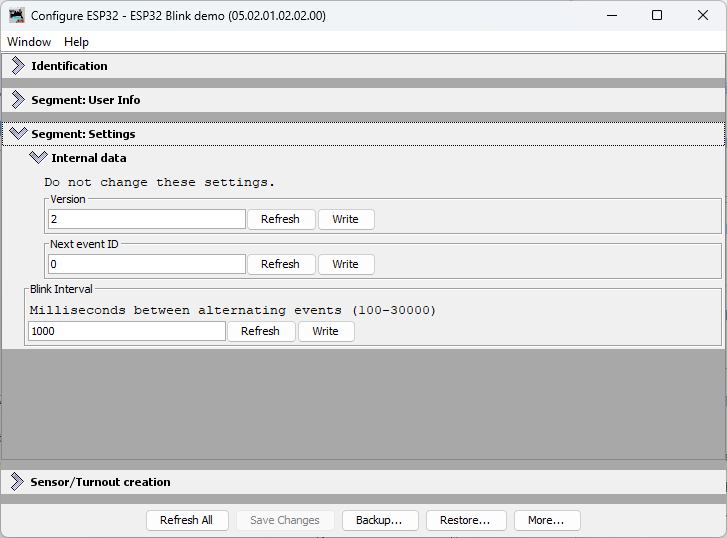

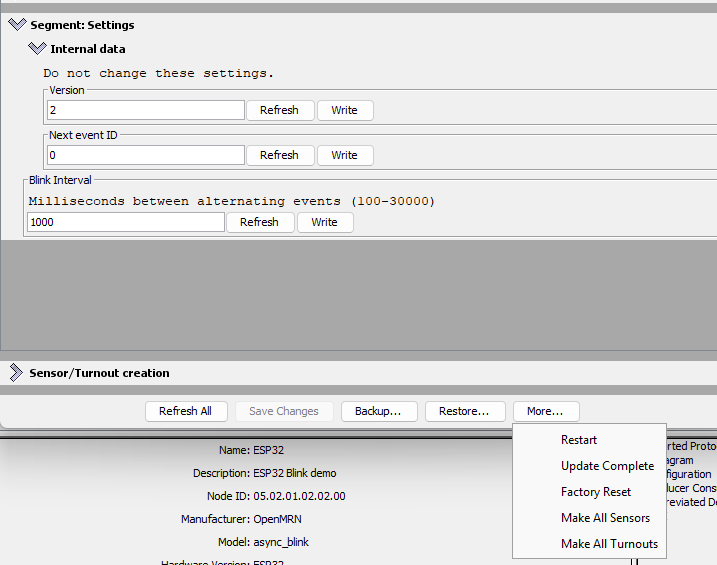

Making These Settings Configurable

The code above uses hardcoded values for the event interval (1 second) and SNIP user data (node name and description). In Chapter 4, you’ll learn how to make these settings configurable via JMRI without recompiling the firmware.

See Chapter 4’s “Adding a Configurable Interval Setting” section to extend this example with runtime-editable parameters, and “Understanding Configuration Updates and Versioning” to understand the mechanisms that make configuration reliable.

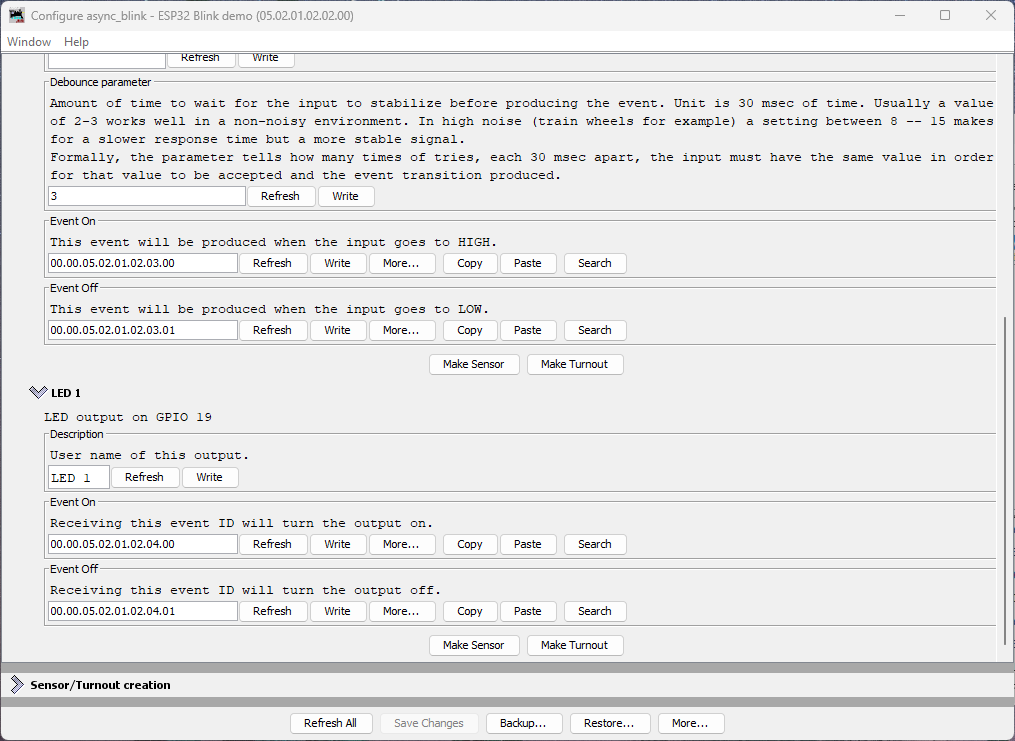

Code Walkthrough

Code Walkthrough

This code is organized into:

- Configuration (config.h): Node identity and CDI structure

- Initialization (setup function with helpers): WiFi, SPIFFS, OpenLCB stack, TCP Hub

- Event production (loop function): Alternate between two events every second

The code includes detailed comments explaining each section. We’ll walk through the key concepts below.

1. Includes and WiFi Configuration

#include <Arduino.h>

#include <WiFi.h>

#include <SPIFFS.h>

#include <OpenMRNLite.h>

#include "config.h"

const char* ssid = "YourWiFiSSID";

const char* password = "YourWiFiPassword";

Required includes:

Arduino.h: Core Arduino frameworkWiFi.h: ESP32 WiFi library for network connectivitySPIFFS.h: ESP32 filesystem library for configuration storageOpenMRNLite.h: OpenLCB protocol stackconfig.h: Our configuration header with CDI definitions

Action Required: Replace ssid and password with your actual WiFi network credentials.

- ESP32 only supports 2.4GHz WiFi networks (not 5GHz)

- SSID is case-sensitive

- This is hardcoded for simplicity - production code would use configuration storage

2. Node and Event IDs

static constexpr uint64_t NODE_ID = 0x050201020200ULL;

static const uint64_t EVENT_ID_0 = 0x0502010202000000ULL;

static const uint64_t EVENT_ID_1 = 0x0502010202000001ULL;

Node ID: Every OpenLCB node must have a globally unique 48-bit identifier. This ID (0x050201020200) is in the experimental range - safe for learning but not for production deployment.

Event IDs: These 64-bit identifiers represent the two events our node will produce. Notice they differ only in the last byte (00 vs 01), making them easy to track. These match the desktop async_blink OpenMRN example for consistency.

3. Configuration and OpenMRN Stack

OpenMRN openmrn(NODE_ID);

static constexpr openlcb::ConfigDef cfg(0);

namespace openlcb {

const char CDI_FILENAME[] = "/spiffs/cdi.xml";

const char CDI_DATA[] = "";

const char* const CONFIG_FILENAME = "/spiffs/openlcb_config";

const size_t CONFIG_FILE_SIZE = cfg.seg().size() + cfg.seg().offset();

const char* const SNIP_DYNAMIC_FILENAME = CONFIG_FILENAME;

}